By Kellen Short

Class of 2010

Anagram analyst. Tile tactician. Linguistic legend.

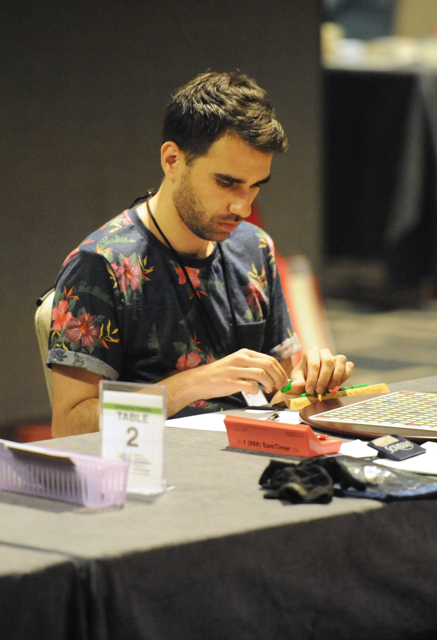

DTH alum Mark Abadi tested his wordsmithery in July at the North American Scrabble Championship in New Orleans, finishing eighth in his division despite several years away from the competition circuit.

“I kind of forgot how much I loved the competition aspect of Scrabble because it had been so long, but I am addicted again,” Mark said.

Mark, a linguistics major, worked for The Daily Tar Heel from 2008-12 as a city writer, city assistant editor, production assistant (where he wrote funny weather forecasts) and columnist. After college he taught English in Malaysia for two years as a Fulbright Scholar. He now lives in New York, where he covers politics (and the occasional linguistics headline) for Business Insider.

How does one become a competitive Scrabble player, exactly?

“I have always been obsessed with word games in general and especially with anagrams,” Mark said. “I’ve always been into that, and I played Scrabble growing up with my parents and never was any good until this time that I learned about the Scrabble Dictionary; I think this was around ninth grade.”

His parents let him use the dictionary during their games, and he finally started winning a few matches as he learned words like “aa,” a type of lava. He later joined the local Scrabble club in Charlotte and played his first tournament in 2007. His metamorphosis from “living room player” to “competitive tournament player” had begun.

So, how does the tournament work?

In the 31-game, five-day championship, competitors are placed into four divisions based on their skill levels and past tournament performances; Division I is most competitive, Division 4 the least. Mark was in Division 3.

Scrabblers play 25-minute games against other players with similar records. Each player keeps track of the tiles in play to try to map out his opponent’s possible moves. In the end, competitors are ranked based on overall record, with point differential as the tiebreaker.

Mark finished eighth out of 89 in his division with an overall record of 19-12. He won $250 and a new dictionary but says he was most proud of the validation he received for his months of preparation.

How did he prepare?

Lots of studying. Mark made flash cards with high-probability words (like the obscure but commonly played “aneroid”) and scrambled the letters to quiz himself. A close friend from his local Scrabble club, who also went to the tournament, helped by playing mock games and texting Mark new words daily.

The preparation paid off when Mark was able to play one of those new words, “entresol,” in competition. Despite not having a clue about the word’s meaning, he got the 50-point bingo bonus, a triple word score and drew a challenge from his opponent, which cost the opponent a turn.

“All that studying paid off for one moment,” he said.

What were the hardest parts?

“I didn’t think that fatigue would be a factor coming into it, but definitely by the end of every day, the last game or two games were some of my worst ones,” Mark said. “There’s only so many tough decisions that one person can make in one day before their brain basically closes up shop.”

Mark’s worst moment came on the second day, when he lost a close game by allowing his opponent to get away with a phony two-letter word.

Does a writing background help your Scrabble game?

Mark actually considers it a disadvantage.

“The people who are the best at Scrabble are math-oriented people and science-oriented people,” he said. “The meanings of the words don’t matter, and secondly, when you get to the highest level, and you’re playing against people who have memorized the dictionary, it’s no longer a game of, ‘What words can I find with my letters?’ It’s a matter of, ‘If I play this word, what opportunities does it open up for my opponent, what probabilities?’”

In fact, Mark has to restrain himself when studying for Scrabble.

“As a lover of words it’s not the best because every time I learn a new word, my first instinct is to look it up and find out what it means and how it’s used and the etymology, and all that stuff is totally useless in Scrabble,” he said.

I feel like this hobby could take over your life. Do you dream about Scrabble?

“I can’t recall any dreams I’ve had, but you are right in saying it’s taking over my life. I’m not even that highly ranked, but thinking about words is all I do,” Mark said. “If I meet someone, I’ll play games in my head, and I’ll try to resist the urge to say like, ‘Oh, Caroline, your name is an anagram of colinear.’”

“It almost ruins board games for me in a way because I only go by the Scrabble dictionary now. I can’t play a normal game of Boggle now because I know so many obscure words that have no purpose in life.”

Any tips for improving my Scrabble game?

· Memorize all 105 two-letter words: “You can learn those words in an afternoon if you want to, because you already know 70 of them, you just don’t know they’re good yet,” Mark said, noting that words like yo, ow, and do, re, mi, fa, so, la and ti all count. “Once you know them it opens up so many opportunities.”

· Vowel dumps: Remember words like audio, queue and luau to free yourself of a bad rack with too many vowels.

· Learn the bingos: The best way to score is to use all seven tiles in one move, a “bingo” that nets a 50-point bonus. Improve your bingo-finding skills by looking for common prefixes and suffixes like “re-“ or “un-“ and “-ed” or “ing,” Mark said. “A rack like DGFILNO can be intimidating, but once you separate the ING it becomes a lot easier to spot ‘folding.’” The Scrabble Cheat Sheet can also help you learn some of the most common arrangements.

· Read “Word Freak” by Stefan Fatsis: The book, which Mark credits with building his interest in the game, chronicles the development of Scrabble and the obsessives who play competitively.

· Find a club or tournament in your area. Learn more about Mark’s tournament appearance in his 96.9 FM “The Beat of Sports” radio interview and his piece in Business Insider.