By Megan Royer

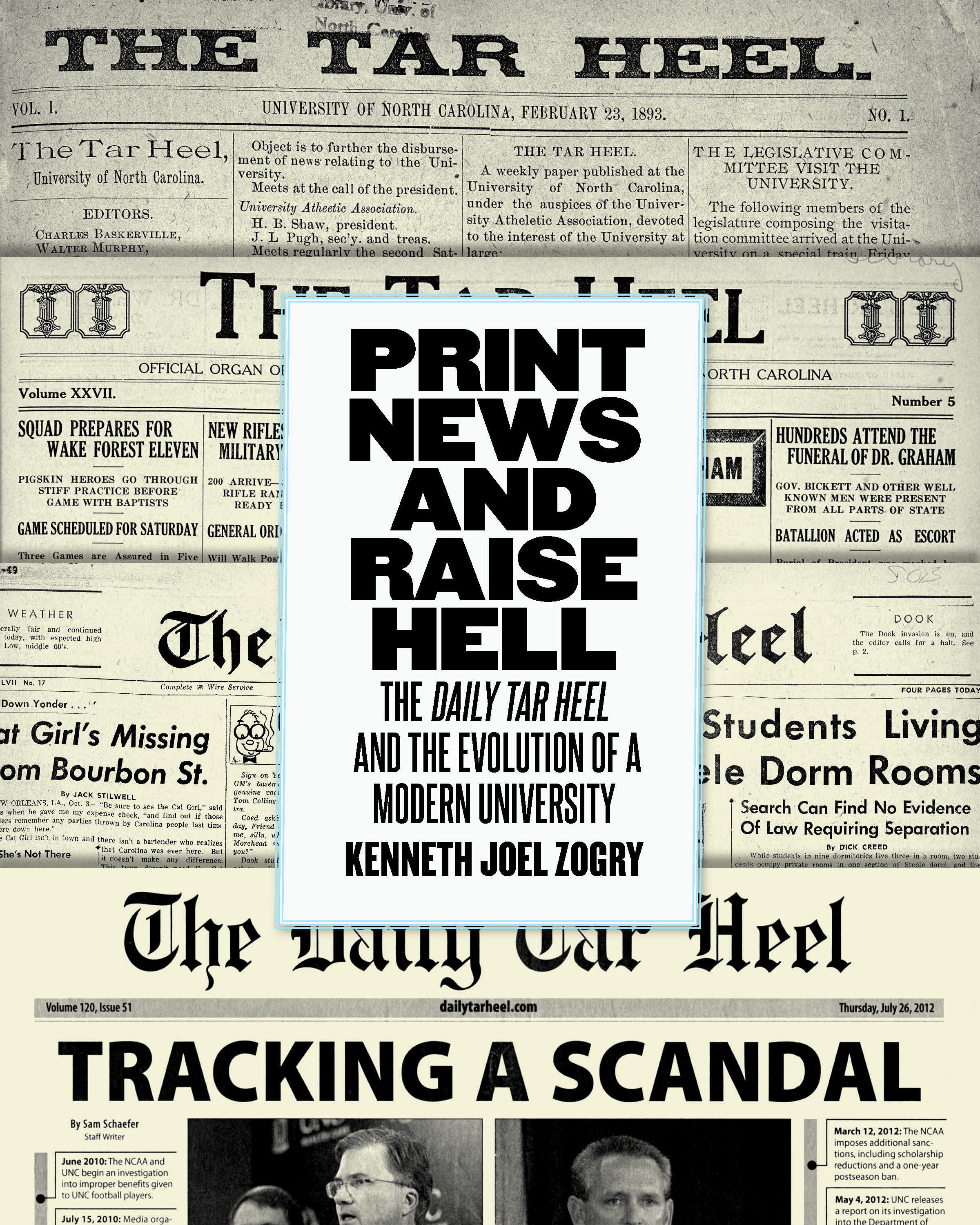

Kenneth Zogry, Ph.D., is an academic and public historian who received his B.A in political science from NC State University and his M.A. and Ph.D. in American history from UNC Chapel Hill. His upcoming book “Print News and Raise Hell: The Daily Tar Heel and the Evolution of a Modern University.” The book explores themes like academic freedom, freedom of speech, freedom of press, sports and the history of sports, race and women – all through the lens of UNC becoming a modern research university.

The book will launch at the #DTH125 weekend Feb. 23-25. Ken sat down with Megan Royer from 1893 Brand Studio to answer some questions about this project.

MR: The DTH was founded 125 years ago. What was UNC like during that time?

KZ: The university reopened after the Civil War in 1875, and the DTH was founded in 1893 as a part of the new modern university, as it was finding its way into becoming a research university. It was tiny – it had under 1,000 students at the time the paper started, and it didn’t really start to grow until the ’20s and ’30s and then exploded after World War II. It wasn’t called “The Daily Tar Heel” until 1929, because it came out sporadically. A year or so after paper started, a group of students who were not happy about it formed a rival newspaper called The White and Blue. They represented the way the old university was, and the DTH represented the new university. The fight was between these two groups of students as to what the university should be.

The DTH has alway been an important force on campus and the paper has always been ahead of the curve (politically), pushing the university in many ways, and was quite influential. At one point it was seen as an equal to some of the major state papers like The News & Observer.

[In 1893, the] school is very small. All male. All white. Incredibly rural. No paved streets, dorms don’t have electricity and are just getting running water. These are really primitive conditions. Do you know what the largest number of ads were during this time? This is so bizarre. Guns and ammunition. Everybody came packing heat! They’re all carrying guns around. Their concept of firearms was so different. You had 16-, 17-, 18-year-olds coming to campus packing heat. But the university was very different, very small– it had under 20 buildings in the 1890s. There was no school of journalism. I write extensively about how the paper was pushing for the journalism school.

MR: What are some things today’s students might recognize on campus or in the paper?

KZ: Almost nothing. If you look at the very first issues (of the DTH), there is no photography. (Photography) was invented but expensive, but there are some drawings. They didn’t believe in headlines, and there were no bylines. Even editorials went unsigned. Physically, papers look very very different. They were all black and white, no color at all; it was very expensive.

A few things that would be the same are that you have a banner, front page stories and an editorial section. The paper didn’t deal with world stories, more just campus news.

MR: You read, or at least skimmed, thousands of editions of the DTH while reading this book. How has it changed? What were you surprised to learn?

KZ: As I was trying to crack the code for how to write about the history of the DTH, I read, or at least skimmed, over 20,000 issues. There’s no other way to do it.

It was interesting to pinpoint that it was during the 1960s that the DTH became what I call an activist publication. Even before that, the paper had always promoted certain ideas. I was surprised to learn that so much of what we deal with today, whether it’s the relationship between state politics and the legislature, sports, issues of race inequality, they all have precedents that go back, in some cases, a century or more. People forget that almost all of these fights have occurred before. I believe as a historian we can learn from the past. Right now I’m working with the Campus Y’s history to learn how students reacted and protested to injustice and how are some students more successful at achieving justice than other instances, over time. It’s like the old saying “history repeats itself.” The clothes change and the music changes, and even the format changes, but so much of the human condition remains the same.

MR: In the book, you pull out main themes that have run through the DTH’s coverage over the years, including the role of athletics on campus and civil rights. How did you identify those themes as important, and what story do they tell about the last 125 years of UNC?

MR: In the book, you pull out main themes that have run through the DTH’s coverage over the years, including the role of athletics on campus and civil rights. How did you identify those themes as important, and what story do they tell about the last 125 years of UNC?

KZ: I’m not a journalist. I’m a historian, and so the training is very different. I’m trained to look at the context. There are certain skills you’re taught about how to identify themes and trends. Some of it– imagine my shock – and they’re complaining about guys playing on the football team who are not real students enrolled in the university. There was fighting in the 1890s on how to regulate sports after they came on campus. There was a huge scandal – the Dixie Classic Scandal– in the ’60s where it got so bad that Bill Friday (the UNC system president at the time) shut down a popular tournament. The mafia gets involved, they are controlling betting across the country. They began to infiltrate top-tier teams and pay the players to shave points. It got down to Carolina and other schools, and the mafia pulls guns on the players in the locker room! I conducted interviews with Bill Friday, who helped me frame the book. I make the argument that this newspaper, in whatever form, is a critical element at a free public university. Free press is the cornerstone of democracy. I’m hoping people get that out of it.

The number one thing was the whole business about sports. It shocked me to go back to the 1890s. People tend to forget the problems and scandals that go with sports. I tracked the beginnings of intercollegiate sports, and the DTH was actually created as a result of this. The university closed after the Civil War, but after it reopened, there was a debate on what type of university UNC should be. It reopened with the goal to be a research institution, one of the first in the South to do this. Intercollegiate sports had come about right at the time of the Civil War, at places like Harvard and Yale, and sports represented this new model. Originally, sports had nothing to do with the university, it was all handled without university supervision. The original athletic association, which was students, founded the DTH to promote the sports. The DTH is intimately tied with sports. The first editor was not an undergraduate student, he was a graduate student, and the quarterback of the football team. It was very incestuous.

MR: How would you sum up the relationship between UNC and the DTH over the years?

KZ: You can’t really answer that question. The relationship has changed a lot over the years, and they had a different relationship at different times. The relationship now is likely more adversarial than it has been in the past; however, that said, there are points of time where there’s been an adversarial relationship regarding sports. In 1953, (a DTH writer) uses the word “cancer” in a headline in an article about sports. It’s very clear (during this time) sports, while problematic, bring money into the university, and how dare someone question that, let alone a student. He accidentally ran across the story and heard there was a special scholarship fund from Student Stores, and (the scholarship money) was being funneled to the football players. He exposed this in the editorial, and that’s why he called it a cancer. There was a lot of tension.

By the late 1960s when there are arguments on whether paper is too liberal, there’s members of the university administration who try to minimize the impact of the paper, and there were several attempts to shut the newspaper down. Part of the reason the paper is separate now is they didn’t want to deal with that any more. Kevin Schwartz (a former general manager) engineered separation from the university, which changed the relationship in 1993, when the paper became as separate entity. It had freedom of information and could then go after the university.

The university and the paper are sort of known as “crazy liberal” and something I worked very hard to very carefully track how much that is true. … There were times at which there were very conservative editors and columnists, and I try to focus on that for balance, but most of the time it’s slightly left of center.

“Print News and Raise Hell: The Daily Tar Heel and the evolution of a modern university” is being published by UNC Press and will be available in as a hardcover and an e-book in February 2018. The book will be sold for $39.95. A book launch event will be held Friday, Feb. 23 at Graham Memorial during the #DTH125 homecoming weekend.